We get attached. It is part of being human. We attach ourselves emotionally to everything from our first teddy bear, to our favourite football team, to our country. Attachment creates at sense of identity and cohesion – ‘I am an engineer’ and ‘I am English’. Attachment helps create stability – ‘This who we are and how we do things around here’. Attachment is a good thing. Except in times of significant change, when it can become a major barrier. Indeed, if we don’t handle it with care, people will stick to a system that is obviously failing rather than accept change.

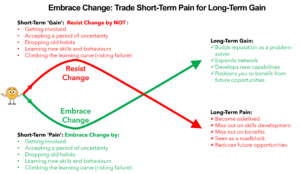

Why it is so hard to let go of the ‘tried and trusted’ in favour of the new? What are the false assumptions that cause so much difficulty? How can we re-frame the situation to smooth the way to necessary change?

Organizational change is often perceived as an attempt to dump existing methods in favour of a new fad or untested idea. Seen in this light, leaders can seem disrespectful of the past and reckless about the future. After all, the old methods are what got us where we are today, why throw them out like so much trash? This is particularly difficult to take if we identity strongly with the status quo. But such views are based on the false assumption that change is a one-off break with all that went before it.

Another closely related assumption is that change is about who is right and who is wrong. In other words, by accepting new ideas as being ‘right’, we must accept that the old ideas were ‘wrong’.

The third and final assumption is that emotions should to be left that the door when we arrive at work, and we should not expect leaders to have to manage the complex feelings associated with change. After all, they are not paid to be psychologists.

So how do we overcome these false assumptions?

First off, we must take a step back from the situation to gain a wider perspective, seeing the present moment as just one single staging-post on much a long journey.

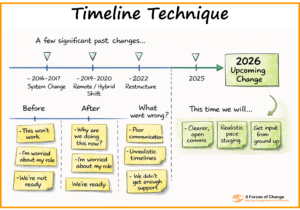

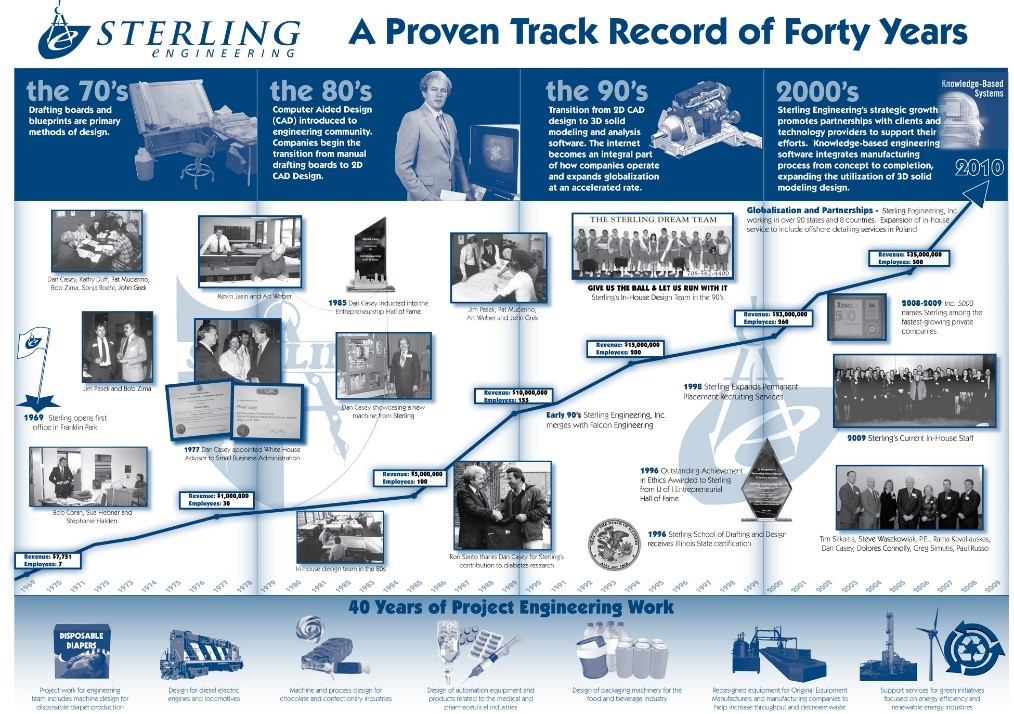

Many organisations celebrate their history with large timeline posters, such as the one depicted here, displayed prominently in head office corridors. These histories are usually punctuated by key moments, such as acquisition of a competitor company or the launch of a major innovation. Looking back on these milestones with the benefit of hindsight, each appears to be an inevitable and necessary feature in the story of the organization’s progression. But at the time, these turning points were most likely characterized by high emotion, excitement and a lot of anxiety. From the perspective of a member of staff, they may well have seemed like an abandonment of the past. That is why walking through the history of past changes and the challenges they involved is a useful way of helping people to put today’s changes into perspective and reminds them that yesterday’s transitions, which now seem so inevitable actually, felt like scary upheavals at that time. We should reflect on the words of a fabled Persian monarch ‘This too shall pass’.

By studying historical changes, we can better appreciate how, in the past, we have innovated and adapted to changes in the world around us in order to avoid falling behind the competition or the world at large. So, change is not a matter of admitting that the old ways were ‘wrong’, it is a matter of recognising that they served us well in the old world, and we should not be afraid to adapt and change again to meet new challenges head-on so we can succeed in the future.

Finally, let’s look at some straightforward, practical ways of handling the emotions associated with letting go other the past. The first tool we can use is the Timeline Technique, introduced above, and explained in greater detail in The 5 Forces of Change. This method offers people a new perspective, in which change is understood to be part of a continuous process of evolution rather than a one-off revolution.

A second, and complimentary approach, is to involve people in identifying what they believe they will lose, keep and gain through a forthcoming change. This helps reframe the change by enabling people to see how much will stay the same after the change and also how they will benefit from it (something that can get lost amongst the angst of change). But, perhaps most important of all, it gives people an opportunity to express their concerns and to be listened to. By getting issues out into the open they can then be discussed and addressed. False assumptions can be challenged, real concerns mitigated and some losses weighed up against gains and the underlying imperative to change.

One further technique – the use of ceremony to help people break with the past – will be covered in my next blog.