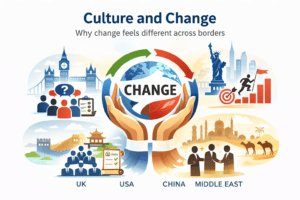

Global organisations often pride themselves on their ability to roll out change at scale. New operating models, systems, and strategies are designed centrally and then deployed across countries with impressive efficiency. On paper, it looks like progress. On the ground, it often feels very different. Global Change Rarely Feels Global to Employees.

In my experience, many cross-border change efforts struggle not because the change itself is flawed, but because leaders underestimate how differently change is experienced from one country to another. The work of Hofstede, and more recently organisations such as The Culture Factor, helps explain why this happens – not as an academic exercise, but as a practical reality of organisational life.

National culture quietly shapes what people expect from leaders, how safe it feels to question decisions, how much explanation is enough, and how quickly people are prepared to commit. When those expectations are overlooked, even well-designed change can stall.

The UK: Polite Agreement Is Not the Same as Commitment

In the UK, change tends to be interpreted through a strong expectation of involvement and explanation. People often want to understand the reasoning behind decisions and to feel that their perspective has been considered, even if it doesn’t ultimately shape the outcome.

In practice, this means resistance is rarely loud. Instead, it shows up as hesitation, cautious compliance, or slow adoption. In my experience, leaders who mistake po

The United States: Energy Is the Currency of Change

In the United States, change frequently gains traction through pace and clarity. People often look for a compelling direction, clear ownership, and visible progress. There is typically a strong appetite for action and opportunity, particularly when change is linked to performance and results.

I’ve seen US change initiatives lose impact when leaders over-consult or delay decisions in pursuit of perfect consensus. While involvement still matters, momentum matters more. When energy drops, attention quickly shifts elsewhere.

China: Stability, Direction, and the Weight of Leadership

China presents a very different change environment. Here, people often assess change through signals from senior leadership and through its alignment with longer-term direction. Visible endorsement from the top provides reassurance and legitimacy.

In my experience, approaches that rely heavily on open debate or challenge – often effective in Western contexts — can feel uncomfortable or confusing. Change in China tends to progress when leaders provide clear direction, maintain consistency, and demonstrate patience. Trust is built through steadiness, not speed.

The Middle East: Trust Before Transformation

Across much of the Middle East, the success of change is closely tied to relationships and credibility. People often look first at the leaders driving the change: their intent, their authority, and their understanding of local context.

Change efforts gain traction when leaders invest time upfront – building confidence, offering reassurance, and showing respect for established norms. When this groundwork is rushed, compliance may appear high, but genuine commitment remains fragile. In my experience, change here is rarely accelerated by pressure alone.

What This Means for Leaders

The common thread across all of these contexts is simple: change frameworks can be standardised; human expectations cannot.

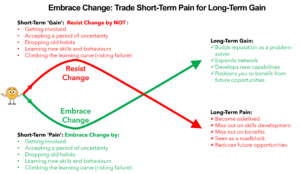

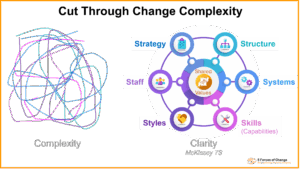

Organisations are very good at replicating tools, processes, and language. They are far less consistent at questioning the assumptions embedded within them — assumptions about voice, authority, risk, and time. When those assumptions clash with local realities, resistance is often misdiagnosed as a performance issue rather than a cultural one.

Effective global change does not require leaders to become cultural anthropologists. It does require curiosity. A willingness to notice when familiar approaches stop working. And the discipline to adapt style without abandoning intent. Global Change Rarely Feels Global to Employees.

A Final Reflection

Perhaps the most important question for leaders implementing change across borders is not “How do we roll this out consistently?” but “Where might our usual approach no longer make sense?”

Because successful change is rarely about doing more things.

It is about understanding people more deeply — especially when their assumptions about work, authority, and change are not the same as our own.

And that understanding is often the difference between change that is formally delivered and change that genuinely takes hold. Global Change Rarely Feels Global to Employees.