The Truth about Resistance

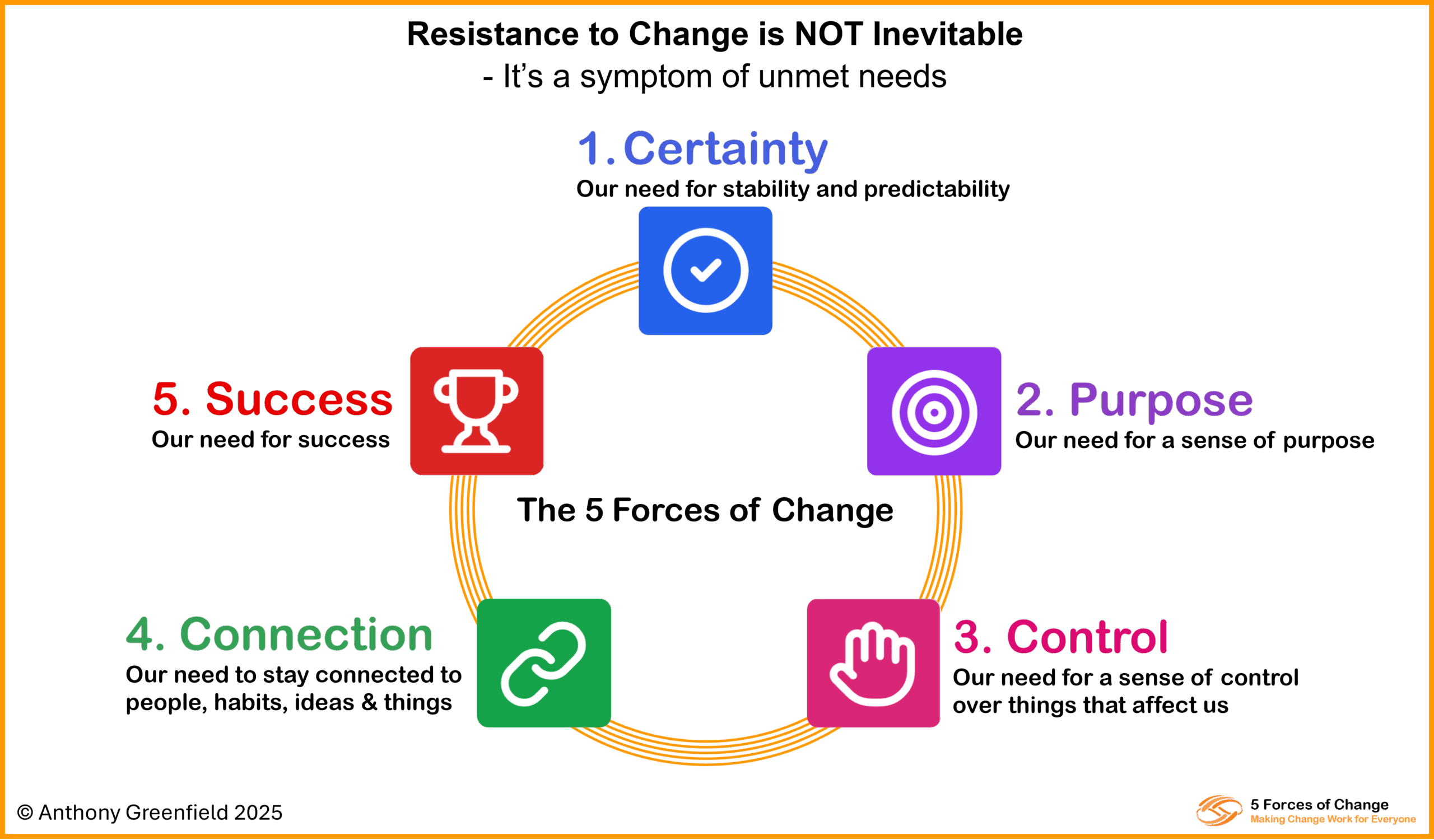

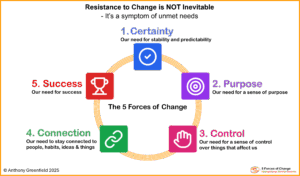

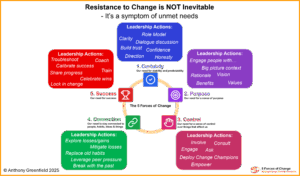

Here’s a truth that many leaders overlook: resistance to change isn’t a character flaw in your people – it’s a predictable response to unmet psychological needs. Resistance to Organisational Change is NOT Inevitable.

When we label employees as “resistant” or “change-averse,” we miss the real issue. People don’t resist change itself. They resist uncertainty, loss of control, and unclear purpose. This distinction matters because it shifts our focus from trying to “overcome” resistance to preventing it in the first place.

The conventional approach to change management treats resistance as an inevitable obstacle to be managed, pushed through, or worked around. We create communication plans to “sell” the change. We develop strategies to “deal with” resistors. We celebrate quick wins to build momentum against the tide of pushback.

But what if we’re asking the wrong question entirely?

A Different Perspective

Instead of asking “How do we overcome resistance?” we should ask “How are we triggering it in the first place?” This reframe is more than semantic. It acknowledges that leaders play an active role in either creating or preventing resistance through the wa y they design and lead change initiatives.

y they design and lead change initiatives.

The good news? When we understand the psychological drivers behind resistance, we can eliminate most of it before it even begins. This isn’t about manipulation or clever tactics. It’s about genuinely meeting the fundamental human needs that change disrupts.

The 5 Forces of Change Framework

The 5 Forces of Change framework reveals the psychological drivers that determine whether people work for or against organisational change. Address these five forces effectively, and you transform potential resistance into genuine engagement.

1. Certainty

Change destroys certainty. When people cannot see their future role or what success looks like, anxiety triggers resistance. Our brains are wired to perceive uncertainty as threat, activating the same neural pathways as physical danger.

Leaders must work overtime to create certainty through clear vision, honest communication, and visible role-modelling. This doesn’t mean having all the answers – claiming certainty you don’t possess breeds cynicism. Instead, it means providing clarity about what you know, what you don’t yet know, and how you’ll navigate forward together.

Effective leaders paint a vivid picture of the destination whilst being transparent about the journey. They establish clear milestones, define what success looks like at each stage, and consistently update people as the situation evolves. When people can see the path ahead -even if it’s challenging – anxiety decreases and engagement increases.

2. Purpose

Successful leaders maintain an unswerving sense of purpose during change. They communicate the ‘big picture’ context – answering “Why do we need to change?”- whilst drawing people towards a compelling vision of the future. They engage people by showing how change benefits them, their colleagues and the organisation. Without this compelling sense of purpose, people won’t sustain commitment through the ups and downs of transition.

The most powerful purpose connects to something bigger than operational efficiency or financial targets. It taps into people’s desire to contribute to something meaningful, to grow professionally, or to serve customers better. When people see how their efforts fit into a larger narrative that matters, they find the resilience to persist through difficulty.

4. Control

Imposed change triggers rebellion. It’s a fundamental psychological principle: people want change done by them, not to them. When leaders announce fully formed plans and expect passive implementation, they strip people of agency and autonomy – two critical psychological needs.

Participation in shaping and implementing change gives people ownership and control over their destiny. Yes, this takes more time upfront. The temptation to “just decide and move forward” is strong, especially under pressure. But the payoff – genuine commitment, creative problem-solving, and sustained engagement – far outweighs the investment.

Having “skin in the game” transforms critics into champions. When people contribute ideas, help solve problems, and see their fingerprints on the solution, they defend it rather than undermine it. The change becomes “ours” rather than “theirs.”

This doesn’t mean running change by committee or seeking consensus on everything. Leaders still need to lead. But it does mean creating genuine opportunities for input, being transparent about which decisions are open for influence, and visibly incorporating people’s contributions where possible.

4. Connection

We become attached to our routines, colleagues, workspaces, and familiar ways of operating. These connections provide comfort, identity, and meaning. Breaking these attachments causes genuine grief – a fact that leaders often underestimate or dismiss.

Successful change requires helping people let go of old connections whilst systematically building new ones. This means acknowledging what’s being lost, creating space for people to process endings, and celebrating what worked in the past even as you move towards the future.

Equally important is establishing new connections to replace what’s being left behind. New habits need time and repetition to feel natural. New relationships need intentional cultivation. New ways of working need practice and support before they feel comfortable.

Without this work, people will unconsciously drift back to old behaviours. The change may happen on paper but not in practice. Leaders must act as architects of both disconnection and reconnection, honouring the past whilst deliberately building the new.

5. Success

Change knocks confidence. Even competent, accomplished people worry about performing well in unfamiliar territory. The learning curve feels uncomfortable. Early mistakes seem magnified. The temptation to revert to old ways – where we felt competent – intensifies with each struggle.

Leaders must nurture achievement through peer support, coaching, celebration of wins (however small), and swift problem-solving when issues arise. This means staying close to the front lines during implementation, noticing and acknowledging progress, and helping people reframe setbacks as learning rather than failure.

Building confidence builds commitment. As people experience success in the new ways of working – even small successes – their belief in the change grows. They develop new competencies, gather evidence that “this can work,” and become advocates based on their own positive experience.

Conclusions

Resistance isn’t inevitable – it’s a symptom of unmet needs. When leaders deliberately address Certainty, Purpose, Control, Connection, and Success, they eliminate the root causes of resistance before they take hold.

This requires a fundamental shift in how we think about change leadership. Instead of viewing ourselves as change champions battling against resistance, we become change architects who design initiatives that meet human needs. The focus moves from persuasion to understanding, from overcoming to preventing, from managing resistance to creating the conditions for engagement.

The question isn’t “How do we overcome resistance?” It’s “How are we triggering it in the first place?”

Start there, and change becomes something your people drive, not something they endure.